Condé Nast Traveler’s Hanya Yanagihara traveled with India Beat to Jaipur and spend her time exploring the markets and ateliers with Bertie and Victoria Dyer.

Color Me Indian

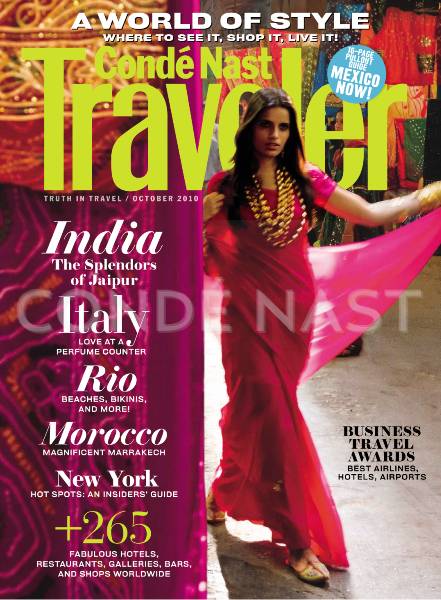

In Jaipur, India’s capital of adornment, there are gems the size of eggs and silks in hues of unimaginable hotness. Hanya Yanagihara arrives packing basic browns and grays. Big mistake–and it’s going to cost her…

Munnu Kasliwal thinks I should wear more diamonds. Diamonds are not just for special occasions, he says. They’re for every day. Take this necklace. Although it’s not so much a necklace as it is a funnel, heavy and stiff and maybe six inches high, with an adjustable silk cord at its back so that it can be cinched snugly about my throat, forcing me to elongate my neck. The front of the piece, facing the world, is an extravagant chain mail of rounded, rose-cut diamonds, hundreds of them, each as big as a child’s fingernail, and each set in soft, nearly pure yellow gold. The other side, which rests against my skin, is enameled in a Mogul-inspired pattern of abstract crimson tulips against a pearlescent white, their petals edged in that same vivid gold. I have never seen—much less touched, much less worn—this many diamonds before, ever.

“This is good for a casual look,” says Munnu, approvingly, as I giddily skip around his second-floor atelier in Jaipur.

Anyone who has been to India—specifically Rajasthan, the rich and kingly region in the country’s northwest—knows that when it comes to adornment, Indians do not think like other people. Munnu is a ninth-generation Jaipur jeweler. For hundreds of years, his family, which includes his brothers—the roguish and charming Sanjay, who also designs fantastic, extravagant pieces, and the elegant Sudhir, who runs their store, the Gem Palace—has made the sort of jewelry that one usually sees only in paintings of seventeenth-century maharajas: astonishingly elaborate creations, dense with rubies and emeralds and diamonds cunningly cut to reflect and glint even in candlelight, and shockingly large gobs of South Sea pearls. This might be why Munnu’s definition of casual is not anyone else’s in the Western world.

Another casual piece he shows me is a rope of quail egg-sized diamonds that you can reverse and wear so that it appears to be merely a length of dark-gold pebbles, each as smooth as a river stone. “You could wear this on the subway in New York and no one would know!” Munnu says.

“I don’t think so,” I say, although for a delirious, senseless second or two, I wonder how much the necklace is worth: More than my mortgage? Could I move somewhere cheaper? I feel myself drifting into a fugue state of insanity. Munnu, who has no doubt seen this vacant expression—half lust, half stupidity—on dozens of women, just laughs.

In New York, where I live, and in many other cities around the world as well, clothing is also about self-expression—but, just as often, it is about anonymity. I packed three dresses for my Jaipur trip. One was brown. Two were gray. In New York, they would have looked appropriate, but in India, where even the camels that clop slowly along the narrow roadways wear saddles of silver-stitched lipstick-red cotton, they seemed wan and apologetic, as leeched of color as the desert that surrounded me.

So much of what is singular and memorable about India is the colors. No religion makes more use of color than Hinduism, with its blue-skinned gods and peony-lipped goddesses, and even the spring festival of Holi is focused on color: Boys squirt arcs of dyed water on passersby, or dump powder, all violently hued, on their marks. In Rajasthan, though, the color comes not from the landscape, which for the most part unfolds in a great unbroken sea of olive and khaki, but almost exclusively from the people. Here, color seems to be humanity’s way of asserting itself against a pitiless and unvaried backdrop. In other places where people embrace color to the same extent—Thailand, for example, or Hawaii—it’s a way of echoing nature’s splendor. In India, the flashes of color seem defiant, the hues brighter, more extreme, better than anything nature could have imagined. The women wear saris in shades that allude not to what’s around them—sand, sky, water—but to jewels or candies or the sticky-sweet sherbets I drank to cool down on the hot afternoons: chartreuse, cherry soda, hot pink, hot blue. All the colors here are hot, even the blues and greens. In Jaipur, the horizon is a long stretch of grit and dross, overlaid with a glittering crust of sequins, rhinestones, and metallic thread.

What is it like, I wondered, to live in a place where ornamentation—in dress, in jewels—is meant for every day; where an outfit is assembled, not tossed on; where jeans have never quite caught on, especially among young women?

Jaipur seemed like the place to go. Although it’s a smallish city by Indian standards, with just 3.2 million people, it is, and has been for centuries, a fashion destination as well. It is one of the world’s most important lapidary workshops—tons of stones pass through the city annually to be cut, polished, carved, and set—and among Indians, it is a popular place to shop for a trousseau, especially the exquisite silk saris that brides wear on their wedding day.

Jaipur, like Florence or Kyoto, other artisan-rich cities to which it roughly compares, has always been known for its craftsmanship. But lately it has become an incubator of its own small group of independent designers, people who are taking traditional, even ancient techniques and fabrications and using them to create something different and new. When we think of an Indian woman, we see a sari—a vague, unspecific sweep of fabric that manages to both conceal and reveal. But saris, like all fashion, evolve: They are not the same from one generation to the next. They too follow trends, and today the trend is for even richer ornamentation, for even more delirious tones, and for silk so fine that it snags on the fingertips.

I was lucky enough to have two guides around the city’s stores and bazaars: Bertie Dyer, who spent much of his childhood in Rajasthan and seemed to know everyone in town, and his wife, Victoria, who, like Bertie, is British and who runs their small, friendly travel agency from their home there.

It was Victoria who introduced me to a young designer, Nidhi Tholia. In her second-floor boutique, Saffron, we watched as she draped one of her saris around the shoulders of an elegant middle-aged woman, a gorgeous trail of silk Georgette in a color Nidhi called watermelon pink, a hue that shaded into a brilliant sunset red, its edges thick with metallic-thread-embroidered peacocks. The woman looked in the mirror and murmured her approval. Later, after she left, Nidhi pulled other pieces off the racks, showing us how she had altered the cut of a traditional salwar kameez dress, fitting it through the bodice but letting it trapeze below the waist, so that it floated away from the body in a cloud of tangerine chiffon. The shop was tiny, just a shoebox with a length of gauzy cotton marking off a dressing room, and when I looked around, I saw not distinct pieces of clothing but instead a blur of shades and textures: It was like being in some sort of enchanted fairyland where every surface whispered across your skin and every color was meant to delight and seduce. Why would an Indian woman ever want to wear jeans and a T-shirt? Of course, the clothes are practical—anyone who has witnessed the creative permutations a woman can invent for her sari knows that—but they are also theatrical, and somehow ceremonious, appropriate for a country and culture that hums with rituals and festivals and holidays.

After we left Nidhi’s shop, Victoria and I went to Hot Pink, one of the city’s best and most interesting boutiques. Set in a small house on the grounds of a prettily ruined little palace, it is stocked with housewares and clothes from some of India’s leading designers. Outside, the air smelled of sugar and loam, like dying flowers. Inside was Sophia Edstrand, the sort of beautiful woman who has an easy, enviable, offhanded chic that proves impossible to duplicate: Her hair was a bright blond, her lips were scarlet, and on each hand she wore a large gold ring, one topped with a clear, pale emerald, the other with a crouching frog carved from a stormy-blue hunk of labradorite, its eyes winking diamond chips.

Sophia was from Sweden, and had worked with Marie-Hélène de Taillac, a jeweler and one of the owners, with Munnu Kasliwal, of Hot Pink. Five years ago, she moved from Paris to Jaipur, and last year she started her own line of accessories, Sophia 203 (the number refers to her favorite Pantone swatch, a bright violet-tinged fuchsia): pochettes and hair bands and necklaces and belts plushly embroidered with butterflies, hearts, stars, and peonies.

Sophia laid the collection out on a low table that had been set with a rainbow of silk scarves, and explained that the threadwork method she used was an old one called zerdogi, mostly practiced, for some reason, by Muslim men. Later, in the airy second-floor room she uses as a factory, I watched as two young, good-looking guys sat cross-legged on rugs, stitching a row of flame-orange butterflies onto black cotton. After the stitchwork was done, the chain of butterflies would be cut from the cloth and mounted onto a strip of velvet, and long tassels would be added so that it could be tied around the waist. “It’s important to continue these traditional crafts or they’ll slowly die out,” Sophia said, as I watched, mesmerized, as the butterflies bloomed against the black.

I have never been one to wear a great deal of color, but it was beginning to seem ridiculous not to. Color, I saw, made everyone look better; color implied that one was vibrant and alert even if it wasn’t true. Sophia watched as I tied on belt after belt. They looked dazzling, even against the mouse gray of my dress. I wished I had some lipstick.

“Lovely,” said Sophia, kindly. “Color suits you.” She was right: It did. Why hadn’t I noticed that before?

I had saved the Gem Palace for the end of my visit, and it was a good thing, for had I started there, I might never have left. And so, after trying on those millions of dollars’ worth of jewels upstairs, I eventually went downstairs, where anyone is allowed to open the many glass-topped cabinets and slip on stacks of gold bangles set with sapphires, or rings fashioned from imperfect, glittering cuts of multihued tourmalines, or fragile strands of gold loops. I finally picked out four loose stones, all tourmalines, each bigger than the last, to be set into rings. “Come by at seven,” Sanjay said. “They’ll be ready by then.”

At seven I was back. The night watchman handed me a manila envelope with my rings inside, each packed in its own burgundy-silk pouch. I put them all on at once. They flashed and sparkled in the dim light.

The next day I headed back toward Delhi, the little van jouncing along India’s famously busy, crowded roads. After a week here, I still marveled at the girl sitting sidesaddle on the back of a motorbike, the ends of her lime-green sari sailing behind her like pennants, and the sight of a lone woman walking the long, lonely stretch between two desolate villages, her sour-lemon sari the brightest thing for miles. Back in New York, I marvel still at recollections like these. But now I have my rings, and the shawl I bought there, a shade of pink not found in nature, and I am trying to wear more color, more jewelry, more everything. When I was in grade school, we were taught the Shaker song “Simple Gifts,” which includes the verse “‘Tis the gift to be simple, ’tis the gift to be free.” Jaipur, though, reminded me that everyday life is not simple but messy, and imperfect, and horribly complicated, and therefore glorious. And what better expression of that glorious imperfection than the self we present to the world. It is what the Indians do so well, and it has bewitched the rest of the world for centuries. ‘Tis a gift to be complicated and colorful and free, they seem to say. Just read my clothes and see.

Victoria Dyer, founder of India Beat, is available for personal shopping tours around Jaipur and can arrange introductions to the cities best designers.

https://www.cntraveler.com/stories/2010-09-10/color-me-indian